HOW WE LEARN

by Terri L. White

Knowledge is acquired through the senses. Although some senses are used more extensively than others, they all play a part in the learning process. Moreover, each person’s learning style determines which senses are most active while acquiring knowledge. This article will serve as an introduction to a series on how we learn; the remainder of the series will explore the individual learning styles.

Sight: Most of our knowledge is obtained through the sense of sight. Diagrams, drawings, models, and pictures are observed and the information is stored in our brains.

Hearing: Hearing enables us to receive instructions and gain from the experiences of others. Surprisingly, reading is considered more related to hearing than to sight.

Touch: Textures, heat and cold, shapes, and degrees of roughness and smoothness are examined by touching. This sense also includes the actual "doing" part of learning.

Smell: To a limited extent, the sense of smell is used in learning, chiefly in recognizing materials, chemicals, etc.

Taste: Obviously the least used of all the senses, taste can play a part in science and home economics.

Experts agree that most people retain approximately:

20% of what we read

20% of what we hear

30% of what we see

50% of what we see and hear

Unfortunately, no studies have yet to determine how much information is retained through the sense of touch. Educators and parents alike, however, are becoming more aware that "hands‑on" activities are crucial to retention for certain learning styles. While these percentages only approximate the extent of learning, they do indicate where to place emphasis in teaching.

Clearly, people retain little of what they only hear or only see, but when teachers combine seeing and hearing, students experience greater retention. Then if one adds "doing" to seeing and hearing, learning becomes even more successful. These “hands-on” activities make learning permanent. People tend to remember more of what they do than what they are told. Thus, increased retention results with more senses involved in the learning process.

A person’s learning style determines the type of instruction best suited for him. Each style accommodates the senses differently. While he is receiving information, the individual can be passive or active, depending on the nature of the instruction. Understanding how we learn unlocks the door to a person’s mind, especially for that hard-to-reach child.

LEARNING STYLES: RECOGNIZING HOW THE MIND WORKS

Learning styles are as unique as finger prints. Numerous specialists have produced models from which we can determine how we best learn. These various models serve us well if we use them cooperatively, and not independently from one another. The different models simply approach learning from different angles. When we "layer" these approaches together, we arrive at a fairly well-rounded understanding of how we learn.

This study focuses on three models: (1) Gregoric Mind-Styles: recognizing how the mind works; (2) Witkin’s Analytic/Global Information Processing: how we understand information; (3) Swassing-Barbe Modality Index: how we remember.

The Gregoric Mind-Styles model explains how the mind works in two ways: (1) Perception: how we take in information; (2) Ordering: how we use information. As individuals we view the world the way it makes the most sense to us, and our perception determines our particular perspective. The Gregoric model outlines two main perceptual attributes found in each person’s mind:

Although every person has both concrete and abstract abilities, individuals tend to be more dominant in one over the other. Persons whose strength is concrete will take in information literally; they will not be looking for the subtle implications like those whose strength is abstract.

As an English major in college, I was constantly challenged to look for the hidden meanings in our literature readings. My "dominant concrete" mind agonized over these assignments. Invariably, I would enlist the help of a "dominant abstract" friend who could painlessly spot the symbolism. Once informed, however, I experienced no difficulty writing the required composition that exposed the hidden meanings of the text.

After taking in information, our minds employ two methods of using or ordering what we know:

One of my sons uses his information in a "dominant random" fashion. During math lessons, he consistently skips steps or devises his own methods for achieving the right answers. It drove my "dominant sequential" mind crazy! However, he will concede to a conventional method when his way will not produce the desired results. In contrast, my other sequentially-oriented son follows the rules to perfection.

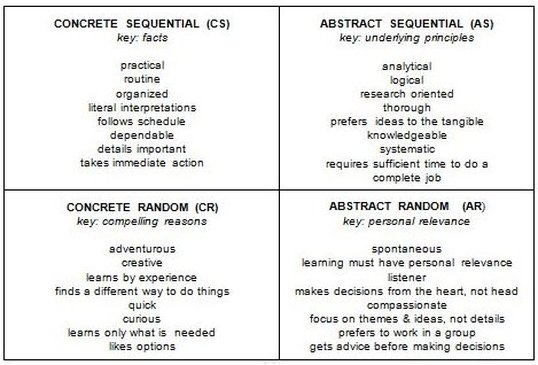

Four dominant learning styles result from combining Gregoric’s perception and ordering definitions. No one style is better or worse than the others; each just includes a different blend of strengths and abilities. While no individual uses only one style, each of us has a dominant style. Below is a list of characteristics of each learning style. As you examine each combination, check off the descriptions under each that most always (not sometimes) applies to you. The learning style with the most checks will be your dominant learning style.

Knowing your children’s and your own learning styles can dramatically change your ability to communicate with each other. For example, understanding that my son is a dominant CR tells me why he skips steps in his math problems. He is not rebelling or trying to annoy me – it is simply the way his brain works. This relieves much tension between Mom and son! Most schools are designed for the sequential thinker; those who order their information randomly appear as rebels or misfits in a system that literally works against them. Understanding these facts gives you the tools with which to help your children succeed in school.

ABSTRACT RANDOM LEARNER

When Candice dejectedly trudged into the classroom, slumped into her seat, and forlornly rested her head in her hands, Nancy’s "antenna" alerted her to the distress. As the teacher began the day’s instructions, Nancy focused on Candice with little thought to the lecture. Hoping to receive permission to talk with Candice while the class settled into their assignments, Nancy scurried to the teacher’s desk. Only when she was satisfied that Candice was comforted, could Nancy concentrate on her studies. An unusual school morning for Nancy? Not at all. For an Abstract Random learner, people are more important than things or learning.

As a people person, an Abstract Random (AR) learner is not only sensitive to the feelings of others, but also easily discouraged if she is not appreciated. With difficulty receiving criticism, she stresses if pressured to be more like a sequential learner, who relishes facts-oriented approaches to learning. A schedule that gives an AR ample time to complete assignments also allows her the flexibility to help others - her top priority. Although adaptable, she focuses on pleasing people by passionately avoiding conflicts. Frequent approval is the fertilizer by which she will bloom.

CUSTOMIZING YOUR AR’S EDUCATION

Curricula preferences for AR learners include writing, literature, foreign languages, social studies, and performing/fine arts. An AR will excel in group learning settings that encourage discussion and role playing rather than competitive approaches. While repetition for the technical details helps her to learn those dreaded facts, enthusiastic presentations that include personal illustrations keep an AR’s attention.

A sequential learner often assumes that an AR is not intelligent because she is not facts-oriented and cannot spit out answers from traditional textbooks or fill-in-the-blank / multiple choice tests. However, what he fails to recognize is that an AR learner tunes into ideas and themes and sees study units and problems as a whole instead of fragmented bits of information. For example, a sequential learner loves to dissect a piece of literature and analyze its parts, but an AR prefers to determine the overall theme or moral and may not even notice the details. Because of this style of learning, a predominate use of oral or essay exams enables an AR to share what she does know since the detailed facts often escape her theme-oriented thinking skills. Routines, drills, and workbooks spell dull, dull, dull to an AR who thrives on spontaneity and creativity. To keep her motivated, let her feel she is contributing something of value and allow her to spread her “creative wings”. Tip for help your AR:

READING:

Prefers: Stories with moral value, fables, parables, and themes in literature (for older students)

Needs help to: Read technical textbooks

Tip: Because AR’s dislike details and may feel overwhelmed with a multitude of rules, choose a phonics program that incorporates games, actions, and songs.

WRITING:

Prefers: Poetry, plays, writing about ethical questions, and creative writing

Needs help to: Tackle reports and research-related writing

Tip: They do not do well with a typical, structured textbook for a language arts curriculum.

MATH:

Prefers: Hands-on math that involves group interaction (playing store) and math games

Needs help to: Drill and repetition

Tip: Problems with life applications motivate AR’s.

SOCIAL STUDIES:

Prefers: Historical novels, biographies, learning about people (their character and their effect on history)

Needs help to: Learn necessary details (dates, etc.)

Tip: Use biographies and library books rather than texts. However, if you must use textbooks, avoid the chapter questions and give students opportunities to share what they do know (orally or with specially designed projects).

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Learning about scientists, their discoveries, and how these affected people; experiments with a group

Needs help to: Pay attention to details

Tip: Use a unit study approach

ARTS:

Prefers: Drawing/painting, art history, illustrating stories, psychological effects of color, interior design, choir, and band.

CONCLUSION

Although an AR will not pursue knowledge for the love of learning, she will be motivated to study to please loved ones or if the information will help her reach a personal goal. Not the most industrious student, she will likely be the most personable. She’ll never be the first to volunteer for cleanup duty because she won’t even notice the mess! Comfortable in clutter, she will surround herself with her creative projects and friends who benefit from her counsel and comfort. To an AR, all of life and learning is an intensely personal experience. Let her enjoy it to the fullest and watch her blossom.

ABSTRACT SEQUENTIAL LEARNER

The stereotyped intellectual is usually caricatured as a rumpled nerd with large, dark horn-rimmed glasses – the "absent-minded professor" type. Alice, on the other hand, is a lovely fifteen-year-old, who not only is clean and neat, but who also radiates a warm smile when you capture her attention. She is, however, the most serious-minded student in her class at the private school she attends. A champion debater and honor roll student, Alice excels in every subject. Because she is quickly bored with repetition and information already mastered, her teacher wisely gives her the freedom to explore the class topic independently. Self-motivated and thirsty for knowledge, Alice always produces a meticulous report for each independent project. A problem solver, she delights in analyzing and exploring, in looking beyond the obvious to find underlying principles and solutions. Since Alice spends most of her time in her various research projects, she lacks well-developed social skills. Often absorbed in thought, her classmates think she is aloof. Friendships do not come easily for Alice because she is an intensely objective person. She never makes a serious commitment in personal relationships until she has all the reliable facts on which to base an emotional involvement. Consequently, the few who make their way into Alice’s world find a covenant-keeping friend. Abstract Sequential (AS) learners like Alice are rare, but their value of wisdom and intelligence adds depth and excellence to our world.

Highly analytic, an AS learner will explore all the options before making a decision. Her natural sense of logic and reason causes her to evaluate virtually everything. This meticulous process takes time; therefore, an AS requires more time than others to fulfill tasks. In fact, she avoids assignments that don’t allow her sufficient time to complete them. Deliberate and systematic in her analysis, an AS derives great joy in not only learning more, but also in the information gathering process itself. An AS rarely verbalizes what she is thinking until she has thoroughly analyzed it and understands the subject to her satisfaction. Afterwards, however, she will give you long answers to short questions, assuming that everyone else wants to know all the facts like she does. She will even monopolize conversations on topics of interest to her. Three words sum up an AS learner: analyze, verbalize, and philosophize.

CUSTOMIZING YOUR AS’s EDUCATION

AS learners dominate math, science, and engineering fields. She delights in student-teacher discussions, but disdains listening to her peers. Lectures, along with question and answer periods, keep her intellect piqued, and she never tires of lively debates or brainstorming sessions. As an objective person, she is uncomfortable with assignments that are too personal. She has difficulty sharing emotions that cannot be explained logically. However, showing an AS why the particular assignment is important will give her a sound reason to cooperate.

An AS learner is naturally suited for long-term and independent projects. If allowed to skip the repetitive material and study in-depth at her own pace, she thrives. Undoubtedly, home schooling is the ideal learning environment for an AS – as long as she is properly challenged and given sufficient time to be thorough. Through sheer boredom, mass education (public and private) normally wilts an AS, unless the teacher makes exceptions for her learning style. Tip for help your AS:

READING:

Prefers: Phonics, mystery stories, reading in subject area of interest, and studying different styles of writing (older student)

Needs help to: Read outside area of interest

Tip: Basic phonics, of necessity, includes much repetition. Since AS learners loathe repetition, find creative ways to keep their interest.

WRITING:

Prefers: Technical writing, grammar, diagramming, structure of language, and word origins.

Needs help to: Write creatively

Tip: A typical textbook approach works well.

MATH:

Prefers: Math principles and theory, real-life problems, math puzzles, and computer

Tip: They will have very little, if any, problems with any math program unless it is too repetitious or does not offer explanations of concepts.

HISTORY:

Prefers: Patterns in history, relationship of math, science, and technology to history, and “what if” questions.

Needs help to: Develop a feeling for the people of history

Tip: Use textbooks with an emphasis on details. Reading biographies balances the events with the people.

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Chemistry and physics, laws and principles of science, solving complex problems, and devising their own experiments.

Tip: Find a challenging text and let her alone!

FINE ARTS:

Prefers: Art – Composition and perspective aspects of art (how/why the artist put together the picture, sculptor, etc. the way he did), print making, and architecture

Music – structure and composition

Needs help to: Develop appreciation for other artistic qualities

Tip: Find lighthearted, fun approaches to the fine arts to help the ultra-serious AS learner relax and lighten-up.

CONCLUSION

An AS learner wants to understand, explain, predict, and control. Highly opinionated, she needs an explanation for everything. Since life is a serious pursuit of knowledge for an AS, she dislikes being rushed in her quest. She blossoms right in the middle of a difficult challenge. Although she will never be the life of the party, the AS can learn viable social skills. Games and outings with family and friends will balance out her serious nature. She will cooperate as long as you give her sufficient time to complete her research projects. As you make the effort to appreciate the depth in your AS, you will understand why she takes time to respond to questions and commitments. She never makes a decision lightly, but always gathers information and weighs it before arriving at a conclusion. Without AS learners, our world would not have its Isaac Newtons, Albert Einsteins, or George Washington Carvers.

CONCRETE RANDOM LEARNER

Charlie was crowned king of the class fidgets. Lectures and instruction manuals bore him. Details drive him to distraction. Conversations without relevance fail to keep his attention. Because he feels confined playing or working on a team, he will often be disruptive. Rules are just guidelines to Charlie, not commandments. As a result, he simply ignores them and charts his own course if the rules offer no relevance to him. Until he can escape to the "real" world and accomplish something of significance, school is a just prison sentence to be endured. At home he usually reads two or more books at a time, but rarely finishes any of them. Cluttered with several unfinished projects, his room is in chaos. A strong-willed child, Charlie resists controls put on his life. It seems that he always has a different opinion than yours. If the family plans to go bowling, Charlie inevitably wants to play putt-putt, if the Dad and Mom choose to go out for pizza, Charlie rallies for hamburgers, ad nauseam. His parents and teachers are at a loss about how to train him.

Does Charlie describe your child? Perhaps he is a mirror image of you! Is Charlie afflicted with the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)? Why is he so difficult and so different from most people? Because traits for ADHD are nearly identical to those that describe a Concrete Random (CR) learning style, many children have been misdiagnosed and drugged simply because they do not learn and think the way most others do. A CR learner is truly a unique individual, one who cannot be forced into a mold. With a little understanding, perhaps we can rescue some children from being channeled into the world of Ritalin.

The CR learner thrives in four main areas: (1) Inspiration – As a visionary, his creativity constantly searches for ways to change the world, to do something better, but the details of actually carrying out the plan bore him. Let him dream and inspire while giving the details to those more suited to making the plan work. (2) Compelling reasons – The CR needs a reason to study a lesson or reach for a goal. If he finds worth in the endeavor, nothing will stop him from completing it. Without a good reason to learn or do something, however, you will find it easier to move a mountain than to motivate your CR to comply. (3) Freedom to choose options – When a CR feels like he has no control over the choices made concerning him, he is very uncooperative. Give him some choices. Ask him if he would rather mow the yard today or tomorrow; this allows him some control over his life. (4) Guidelines instead of rules – The CR’s brain tells him that a rule without a reason to exist does not have to be obeyed. A "DO NOT ENTER" sign on a perfectly good door makes no sense to a CR. Why shouldn’t he enter through that particular door? If the sign instead read "PLEASE DO NOT USE THIS DOOR BECAUSE THE FLOOR INSIDE HAS WET PAINT ON IT," a CR sees the logic and will gladly use a different entrance. Of course, a preschool child should learn to obey without knowing why. Nevertheless, as he matures, it is important for a CR to see the reason behind the rule. In fact, include him in the "framing" of your household rules.

CUSTOMIZING YOUR CR’S EDUCATION

The CR learns best by doing. If he can put his hands on it, he’ll master it. You will find an overflow of Concrete Random learners in music, art, athletics, drama, mechanics, and home economics classes. Games, competition, physical involvement, and freedom to act bring out the best in a CR. Parents and teachers using short, dynamic presentations and audiovisual aids will keep his attention. If a CR has several options from which to choose and then full control of his own project, he will bloom. Since boredom is the CR’s worst enemy, these approaches keep his creativity, resourcefulness, and unpredictable nature channeled in positive directions.

Action-oriented and a visionary, a CR dislikes projects that require considerable planning, detailed records, formal reports, or complicated procedures. Once he has finished an assignment, he balks at redoing it. For example, writing a composition requires several steps of editing which irritates a CR. (Doesn’t everyone know that the first draft is the finished product?!) Workbooks, pencil and paper tasks, and routines bore him to tears, while restrictions and limitations without options stifle him. The fastest way to bring out the worst in a CR is to put him in an "educational straight jacket" – a system that is intolerant of innovative ways to challenge the Concrete Random learner. Tip for help your CR:

READING:

Prefers: Exciting/humorous stories

Needs help to: Concentrate on phonics rules, analyze stories, and reading nonfiction

Tip: When teaching how to read, choose a program that uses games, action, and songs.

WRITING:

Prefers: Stories and poetry (creative writing)

Needs help to: Tackle reports and research-related writing

Tip: They do not do well with a typical, structured textbook for a language arts curriculum.

MATH:

Prefers: Math games; short, varied tasks; practical application; reward system; manipulatives

Needs help to: Do pencil and paper work, develop longer attention span, and do long word problems

Tip: They are very competitive with math games. Many math programs incorporate manipulatives/games into the learning process.

SOCIAL STUDIES:

Prefers: Heroes and adventure; wars in history, action stories, dress-up and acting; travel; map making (especially three-dimensional); making simple dioramas or projects.

Needs help to: Tie together events, people, and places and to understand the relevancy of history to us today.

Tip: Read biographies and historical fiction; avoid dry textbooks. Plan lots of field trips.

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Short, hands-on experiments; outdoor activity; active field trips; life science and wildlife studies

Needs help to: Work with scientific data and work on longer term projects

Tip: Avoid a structured, textbook approach; use a curriculum that involves hands-on learning.

FINE ARTS:

Prefers: Varied, short projects; different media; paper construction; drama and dance; music (usually plays by ear); singing.

CONCLUSION

If a doctor diagnosed your child with ADHD, it might be wise to seek a second opinion. Some doctors do not thoroughly test the children – beware of their diagnosis. Your child may simply be a stressed out CR who has never been appreciated for who he is. Most of us can sit still for long periods and handle monotony, but for a CR – whose life is an adventure – boredom is a prison sentence from which he is determined to break out! According to Cynthia Tobias in The Way They Learn, parents can lessen a CR’s stress by (1) lightening up without letting up, (2) backing off and not forcing the issue, (3) helping him figure out what will inspire him, (4) encouraging lots of ways to reach the same goal, (5) pointing him in the right direction and then backing off (the degree you back off depends on the age of the child), and, (6) most importantly, conveying love and acceptance no matter what. Although your CR’s “feet march to the sound of a different drummer”, allowing him to be himself and appreciating his differences will be the "fertilizer" he needs to grow and blossom into a secure, productive adult.

CONCRETE SEQUENTIAL LEARNER

James is home schooled. His mother stays busy with five children, of which James is the oldest. Conscientious and dependable, James is the least demanding of the children. Early on, Mom noticed that he prefers workbooks to multi-age unit studies. As long as his work space is quiet and clean (which means away from younger siblings), James methodically works through his assignments. Because doing his work correctly is crucial to him, James frequently asks for clarification on instructions. Therefore, to avoid interruptions, Mom never leaves James with an assignment until she is certain he understands. Although James devours facts and churns out perfect scores on exams, he struggles in areas that require abstract thinking. Reading between-the-lines puts him in a cold sweat. If you just give him the facts and let him deal with literal meanings, he’ll even hum while studying! Academically, mass education is designed for Concrete Sequential (CS) learners like James, but he’s happy at home, learning at his own pace and developing values important to his family.

A no-nonsense person, a CS learner sees the practical side of issues. When he speaks, he is never subtle, but goes directly to the point. Not one to quit in the middle of anything, he will finish whatever he is doing even if he hates it. This is because a CS has a sense of order and responsibility that requires a beginning, middle, and an end. Nearly as predictable as the sunrise, you can always count on a CS to follow through. Although not naturally creative, he excels at fine-tuning and improving another’s original idea. A list-maker and organizer, he thrives on a schedule. Consistency is his byword.

Routine is important to a CS learner. When unexpected changes occur, he struggles to adapt. While it is important that he understand life cannot always be predictable, if possible, give him advance notice of a change in plans. Never just tell a CS what to do unless he is already familiar with the task. Provide concrete examples of what is required because vague directions do not register. Often overwhelmed with too much to do, he becomes frustrated by not knowing where to begin. Ask him how you can help him. Sometimes helping him to list priorities is all he needs to get going. While CR or AR learners almost relish clutter and noise, a CS learner’s ability to concentrate freezes in such an environment. If you provide a specific time for uninterrupted work in a clean and quiet place, he’ll sail through his assignments comfortably and come out smiling. He delights to accomplish his goals and check them off his list!

CUSTOMIZING YOUR CS’s EDUCATION

CS learners flourish in math, spelling, history, geography, and business subjects. He relishes drills, reviews, memorization, and thrives on workbooks, structure, and routine. Lectures and outlines neatly place all the facts in his orderly mind to draw out when needed. His mind is a splendid time line! A CS has an innate need for order and a propensity for perfectionism. Because of these traits, he learns best by following an example. Although not too fond of discussions or oral reports, he will excel if given enough time to prepare. Role playing and dramatization, however, are not his forte. He can churn out reports replete with all the facts, but imaginative writing draws a blank in him. Nonetheless, even the driest CS learner can be taught to think creatively. Tangible rewards and hands-on methods motivate him. If you wisely and gently use these types of motivations, you will watch a CS gradually unfold to a new world of creativity. Tip for help your CS:

READING:

Prefers: Phonics, programmed reading, word lists, and oral reading (if they are prepared)

Needs help to: Read from context and read beyond the literal meaning

Tip: Will do well with most phonics programs. Practice oral reading in a nonthreatening, relaxed setting.

WRITING:

Prefers: Handwriting drills, worksheets, and well spelled-out assignments

Needs help to: Write creatively

Tip: He will do well with traditional language art textbooks. For creative writing, though, use "story starters" or books that deal specifically with creative writing.

MATH:

Prefers: Workbooks, programmed math, and drill

Needs help to: Apply arithmetic to word problems that require abstract thinking

Tip: He will do well with most math textbooks

HISTORY:

Prefers: Names, dates, making maps and time lines

Needs help to: Read biographies, historical fiction, and novels that give life to these subjects.

Tip: Because a CS thrives on the details, they miss the big picture. Find creative ways to show him how the details fit together in the overall message. (Read biographies and historical fiction aloud as a family.)

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Science notebooks, collections of leaves, rocks, etc., programmed book learning, and sciences that are less speculative (biology, botany, and physiology)

Needs help to: Form hypotheses and do experiments

Tip: Plan creative projects that let him express his aptitude for details and facts.

FINE ARTS:

Prefers: Art - drawing with clear directions to follow, photography, and crafts;

Music - note reading

Needs help to: Bring out his own creativity

Tip: Drawing with Children by Mona Brooks is an excellent resource that equips the ordinary person to teach art. It teaches how to analyze everything you see so that you can know how to draw. It also includes painting instructions. This style would work well with a CS learner.

CONCLUSION

Your CS learner is the most goal-oriented of all the learning styles. Some will accuse him of tunnel-vision, but this mastery at maintaining focus and drive to fulfill the goal provides our world with men and women who routinely accomplish ordinary and history-making achievements. This trait, however, causes a CS to value things and responsibilities more than people. Knowing this, parents must teach their CS that life does not solely consist of attaining goals; he needs to understand that it is okay to take time for people, too. If necessary, let him schedule time for family and friends on his calendar. He may even feel that he "accomplished" something when he checks it off his list!

As a perfectionist, he will thoroughly fine-tune an idea or project. You can help him to not take himself and life too seriously by teaching him to laugh at himself and the inevitable imperfections of life. Encouraging him to practice patience with the people in his life will make him amiable, also. A slave to routine, your CS is uncomfortable with change. You can rejoice that this characteristic enables you to count on him, and, at the same time, gradually introduce circumstances that require him to adapt. While it is important to teach your CS to relax and enjoy life, remember to appreciate him for who he is: serious, practical, and predictable.

On Monday your son was given a list of twenty-five new words to spell and define by Friday. How is he going to master the words so that he remembers them? Will he put them on flash cards complete with word-association pictures? Perhaps he will record the spelling and definition of each on a cassette to listen to while he does his chores at home. He could even tape the words on twenty-five different pieces of furniture all over the house, timing himself as he races to each word. These are examples of the three basic ways of remembering information: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. We all use each in varying degrees, but will have one style that dominates how we remember. Use the following chart by Cynthia Tobias (The Way They Learn, p. 90) to decide whether you and your children are auditory, visual, or kinesthetic learners. (If you are still unsure which style you are after checking the chart, try out each approach until you find one that fits you.)

Sight: Most of our knowledge is obtained through the sense of sight. Diagrams, drawings, models, and pictures are observed and the information is stored in our brains.

Hearing: Hearing enables us to receive instructions and gain from the experiences of others. Surprisingly, reading is considered more related to hearing than to sight.

Touch: Textures, heat and cold, shapes, and degrees of roughness and smoothness are examined by touching. This sense also includes the actual "doing" part of learning.

Smell: To a limited extent, the sense of smell is used in learning, chiefly in recognizing materials, chemicals, etc.

Taste: Obviously the least used of all the senses, taste can play a part in science and home economics.

Experts agree that most people retain approximately:

20% of what we read

20% of what we hear

30% of what we see

50% of what we see and hear

Unfortunately, no studies have yet to determine how much information is retained through the sense of touch. Educators and parents alike, however, are becoming more aware that "hands‑on" activities are crucial to retention for certain learning styles. While these percentages only approximate the extent of learning, they do indicate where to place emphasis in teaching.

Clearly, people retain little of what they only hear or only see, but when teachers combine seeing and hearing, students experience greater retention. Then if one adds "doing" to seeing and hearing, learning becomes even more successful. These “hands-on” activities make learning permanent. People tend to remember more of what they do than what they are told. Thus, increased retention results with more senses involved in the learning process.

A person’s learning style determines the type of instruction best suited for him. Each style accommodates the senses differently. While he is receiving information, the individual can be passive or active, depending on the nature of the instruction. Understanding how we learn unlocks the door to a person’s mind, especially for that hard-to-reach child.

LEARNING STYLES: RECOGNIZING HOW THE MIND WORKS

Learning styles are as unique as finger prints. Numerous specialists have produced models from which we can determine how we best learn. These various models serve us well if we use them cooperatively, and not independently from one another. The different models simply approach learning from different angles. When we "layer" these approaches together, we arrive at a fairly well-rounded understanding of how we learn.

This study focuses on three models: (1) Gregoric Mind-Styles: recognizing how the mind works; (2) Witkin’s Analytic/Global Information Processing: how we understand information; (3) Swassing-Barbe Modality Index: how we remember.

The Gregoric Mind-Styles model explains how the mind works in two ways: (1) Perception: how we take in information; (2) Ordering: how we use information. As individuals we view the world the way it makes the most sense to us, and our perception determines our particular perspective. The Gregoric model outlines two main perceptual attributes found in each person’s mind:

- Concrete: Information is taken in mainly by the senses and deals with the tangible and obvious.

- Abstract: This ability allows us to visualize, discover hidden meanings, and grasp ideas. One uses his imagination, intellect, and intuition rather than the five senses.

Although every person has both concrete and abstract abilities, individuals tend to be more dominant in one over the other. Persons whose strength is concrete will take in information literally; they will not be looking for the subtle implications like those whose strength is abstract.

As an English major in college, I was constantly challenged to look for the hidden meanings in our literature readings. My "dominant concrete" mind agonized over these assignments. Invariably, I would enlist the help of a "dominant abstract" friend who could painlessly spot the symbolism. Once informed, however, I experienced no difficulty writing the required composition that exposed the hidden meanings of the text.

After taking in information, our minds employ two methods of using or ordering what we know:

- Sequential: Information is arranged in a linear, step-by-step approach. The mind works in a logical sequence and prefers to follow a plan

- Random: The mind organizes information by chunks with no particular sequence. A random mind is impulsive and spontaneous. Rather than follow a plan or a particular sequence, the mind prefers to skip steps, work backwards, or even rearrange the order of the sequence while still arriving at the correct outcome.

One of my sons uses his information in a "dominant random" fashion. During math lessons, he consistently skips steps or devises his own methods for achieving the right answers. It drove my "dominant sequential" mind crazy! However, he will concede to a conventional method when his way will not produce the desired results. In contrast, my other sequentially-oriented son follows the rules to perfection.

Four dominant learning styles result from combining Gregoric’s perception and ordering definitions. No one style is better or worse than the others; each just includes a different blend of strengths and abilities. While no individual uses only one style, each of us has a dominant style. Below is a list of characteristics of each learning style. As you examine each combination, check off the descriptions under each that most always (not sometimes) applies to you. The learning style with the most checks will be your dominant learning style.

Knowing your children’s and your own learning styles can dramatically change your ability to communicate with each other. For example, understanding that my son is a dominant CR tells me why he skips steps in his math problems. He is not rebelling or trying to annoy me – it is simply the way his brain works. This relieves much tension between Mom and son! Most schools are designed for the sequential thinker; those who order their information randomly appear as rebels or misfits in a system that literally works against them. Understanding these facts gives you the tools with which to help your children succeed in school.

ABSTRACT RANDOM LEARNER

When Candice dejectedly trudged into the classroom, slumped into her seat, and forlornly rested her head in her hands, Nancy’s "antenna" alerted her to the distress. As the teacher began the day’s instructions, Nancy focused on Candice with little thought to the lecture. Hoping to receive permission to talk with Candice while the class settled into their assignments, Nancy scurried to the teacher’s desk. Only when she was satisfied that Candice was comforted, could Nancy concentrate on her studies. An unusual school morning for Nancy? Not at all. For an Abstract Random learner, people are more important than things or learning.

As a people person, an Abstract Random (AR) learner is not only sensitive to the feelings of others, but also easily discouraged if she is not appreciated. With difficulty receiving criticism, she stresses if pressured to be more like a sequential learner, who relishes facts-oriented approaches to learning. A schedule that gives an AR ample time to complete assignments also allows her the flexibility to help others - her top priority. Although adaptable, she focuses on pleasing people by passionately avoiding conflicts. Frequent approval is the fertilizer by which she will bloom.

CUSTOMIZING YOUR AR’S EDUCATION

Curricula preferences for AR learners include writing, literature, foreign languages, social studies, and performing/fine arts. An AR will excel in group learning settings that encourage discussion and role playing rather than competitive approaches. While repetition for the technical details helps her to learn those dreaded facts, enthusiastic presentations that include personal illustrations keep an AR’s attention.

A sequential learner often assumes that an AR is not intelligent because she is not facts-oriented and cannot spit out answers from traditional textbooks or fill-in-the-blank / multiple choice tests. However, what he fails to recognize is that an AR learner tunes into ideas and themes and sees study units and problems as a whole instead of fragmented bits of information. For example, a sequential learner loves to dissect a piece of literature and analyze its parts, but an AR prefers to determine the overall theme or moral and may not even notice the details. Because of this style of learning, a predominate use of oral or essay exams enables an AR to share what she does know since the detailed facts often escape her theme-oriented thinking skills. Routines, drills, and workbooks spell dull, dull, dull to an AR who thrives on spontaneity and creativity. To keep her motivated, let her feel she is contributing something of value and allow her to spread her “creative wings”. Tip for help your AR:

READING:

Prefers: Stories with moral value, fables, parables, and themes in literature (for older students)

Needs help to: Read technical textbooks

Tip: Because AR’s dislike details and may feel overwhelmed with a multitude of rules, choose a phonics program that incorporates games, actions, and songs.

WRITING:

Prefers: Poetry, plays, writing about ethical questions, and creative writing

Needs help to: Tackle reports and research-related writing

Tip: They do not do well with a typical, structured textbook for a language arts curriculum.

MATH:

Prefers: Hands-on math that involves group interaction (playing store) and math games

Needs help to: Drill and repetition

Tip: Problems with life applications motivate AR’s.

SOCIAL STUDIES:

Prefers: Historical novels, biographies, learning about people (their character and their effect on history)

Needs help to: Learn necessary details (dates, etc.)

Tip: Use biographies and library books rather than texts. However, if you must use textbooks, avoid the chapter questions and give students opportunities to share what they do know (orally or with specially designed projects).

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Learning about scientists, their discoveries, and how these affected people; experiments with a group

Needs help to: Pay attention to details

Tip: Use a unit study approach

ARTS:

Prefers: Drawing/painting, art history, illustrating stories, psychological effects of color, interior design, choir, and band.

CONCLUSION

Although an AR will not pursue knowledge for the love of learning, she will be motivated to study to please loved ones or if the information will help her reach a personal goal. Not the most industrious student, she will likely be the most personable. She’ll never be the first to volunteer for cleanup duty because she won’t even notice the mess! Comfortable in clutter, she will surround herself with her creative projects and friends who benefit from her counsel and comfort. To an AR, all of life and learning is an intensely personal experience. Let her enjoy it to the fullest and watch her blossom.

ABSTRACT SEQUENTIAL LEARNER

The stereotyped intellectual is usually caricatured as a rumpled nerd with large, dark horn-rimmed glasses – the "absent-minded professor" type. Alice, on the other hand, is a lovely fifteen-year-old, who not only is clean and neat, but who also radiates a warm smile when you capture her attention. She is, however, the most serious-minded student in her class at the private school she attends. A champion debater and honor roll student, Alice excels in every subject. Because she is quickly bored with repetition and information already mastered, her teacher wisely gives her the freedom to explore the class topic independently. Self-motivated and thirsty for knowledge, Alice always produces a meticulous report for each independent project. A problem solver, she delights in analyzing and exploring, in looking beyond the obvious to find underlying principles and solutions. Since Alice spends most of her time in her various research projects, she lacks well-developed social skills. Often absorbed in thought, her classmates think she is aloof. Friendships do not come easily for Alice because she is an intensely objective person. She never makes a serious commitment in personal relationships until she has all the reliable facts on which to base an emotional involvement. Consequently, the few who make their way into Alice’s world find a covenant-keeping friend. Abstract Sequential (AS) learners like Alice are rare, but their value of wisdom and intelligence adds depth and excellence to our world.

Highly analytic, an AS learner will explore all the options before making a decision. Her natural sense of logic and reason causes her to evaluate virtually everything. This meticulous process takes time; therefore, an AS requires more time than others to fulfill tasks. In fact, she avoids assignments that don’t allow her sufficient time to complete them. Deliberate and systematic in her analysis, an AS derives great joy in not only learning more, but also in the information gathering process itself. An AS rarely verbalizes what she is thinking until she has thoroughly analyzed it and understands the subject to her satisfaction. Afterwards, however, she will give you long answers to short questions, assuming that everyone else wants to know all the facts like she does. She will even monopolize conversations on topics of interest to her. Three words sum up an AS learner: analyze, verbalize, and philosophize.

CUSTOMIZING YOUR AS’s EDUCATION

AS learners dominate math, science, and engineering fields. She delights in student-teacher discussions, but disdains listening to her peers. Lectures, along with question and answer periods, keep her intellect piqued, and she never tires of lively debates or brainstorming sessions. As an objective person, she is uncomfortable with assignments that are too personal. She has difficulty sharing emotions that cannot be explained logically. However, showing an AS why the particular assignment is important will give her a sound reason to cooperate.

An AS learner is naturally suited for long-term and independent projects. If allowed to skip the repetitive material and study in-depth at her own pace, she thrives. Undoubtedly, home schooling is the ideal learning environment for an AS – as long as she is properly challenged and given sufficient time to be thorough. Through sheer boredom, mass education (public and private) normally wilts an AS, unless the teacher makes exceptions for her learning style. Tip for help your AS:

READING:

Prefers: Phonics, mystery stories, reading in subject area of interest, and studying different styles of writing (older student)

Needs help to: Read outside area of interest

Tip: Basic phonics, of necessity, includes much repetition. Since AS learners loathe repetition, find creative ways to keep their interest.

WRITING:

Prefers: Technical writing, grammar, diagramming, structure of language, and word origins.

Needs help to: Write creatively

Tip: A typical textbook approach works well.

MATH:

Prefers: Math principles and theory, real-life problems, math puzzles, and computer

Tip: They will have very little, if any, problems with any math program unless it is too repetitious or does not offer explanations of concepts.

HISTORY:

Prefers: Patterns in history, relationship of math, science, and technology to history, and “what if” questions.

Needs help to: Develop a feeling for the people of history

Tip: Use textbooks with an emphasis on details. Reading biographies balances the events with the people.

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Chemistry and physics, laws and principles of science, solving complex problems, and devising their own experiments.

Tip: Find a challenging text and let her alone!

FINE ARTS:

Prefers: Art – Composition and perspective aspects of art (how/why the artist put together the picture, sculptor, etc. the way he did), print making, and architecture

Music – structure and composition

Needs help to: Develop appreciation for other artistic qualities

Tip: Find lighthearted, fun approaches to the fine arts to help the ultra-serious AS learner relax and lighten-up.

CONCLUSION

An AS learner wants to understand, explain, predict, and control. Highly opinionated, she needs an explanation for everything. Since life is a serious pursuit of knowledge for an AS, she dislikes being rushed in her quest. She blossoms right in the middle of a difficult challenge. Although she will never be the life of the party, the AS can learn viable social skills. Games and outings with family and friends will balance out her serious nature. She will cooperate as long as you give her sufficient time to complete her research projects. As you make the effort to appreciate the depth in your AS, you will understand why she takes time to respond to questions and commitments. She never makes a decision lightly, but always gathers information and weighs it before arriving at a conclusion. Without AS learners, our world would not have its Isaac Newtons, Albert Einsteins, or George Washington Carvers.

CONCRETE RANDOM LEARNER

Charlie was crowned king of the class fidgets. Lectures and instruction manuals bore him. Details drive him to distraction. Conversations without relevance fail to keep his attention. Because he feels confined playing or working on a team, he will often be disruptive. Rules are just guidelines to Charlie, not commandments. As a result, he simply ignores them and charts his own course if the rules offer no relevance to him. Until he can escape to the "real" world and accomplish something of significance, school is a just prison sentence to be endured. At home he usually reads two or more books at a time, but rarely finishes any of them. Cluttered with several unfinished projects, his room is in chaos. A strong-willed child, Charlie resists controls put on his life. It seems that he always has a different opinion than yours. If the family plans to go bowling, Charlie inevitably wants to play putt-putt, if the Dad and Mom choose to go out for pizza, Charlie rallies for hamburgers, ad nauseam. His parents and teachers are at a loss about how to train him.

Does Charlie describe your child? Perhaps he is a mirror image of you! Is Charlie afflicted with the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)? Why is he so difficult and so different from most people? Because traits for ADHD are nearly identical to those that describe a Concrete Random (CR) learning style, many children have been misdiagnosed and drugged simply because they do not learn and think the way most others do. A CR learner is truly a unique individual, one who cannot be forced into a mold. With a little understanding, perhaps we can rescue some children from being channeled into the world of Ritalin.

The CR learner thrives in four main areas: (1) Inspiration – As a visionary, his creativity constantly searches for ways to change the world, to do something better, but the details of actually carrying out the plan bore him. Let him dream and inspire while giving the details to those more suited to making the plan work. (2) Compelling reasons – The CR needs a reason to study a lesson or reach for a goal. If he finds worth in the endeavor, nothing will stop him from completing it. Without a good reason to learn or do something, however, you will find it easier to move a mountain than to motivate your CR to comply. (3) Freedom to choose options – When a CR feels like he has no control over the choices made concerning him, he is very uncooperative. Give him some choices. Ask him if he would rather mow the yard today or tomorrow; this allows him some control over his life. (4) Guidelines instead of rules – The CR’s brain tells him that a rule without a reason to exist does not have to be obeyed. A "DO NOT ENTER" sign on a perfectly good door makes no sense to a CR. Why shouldn’t he enter through that particular door? If the sign instead read "PLEASE DO NOT USE THIS DOOR BECAUSE THE FLOOR INSIDE HAS WET PAINT ON IT," a CR sees the logic and will gladly use a different entrance. Of course, a preschool child should learn to obey without knowing why. Nevertheless, as he matures, it is important for a CR to see the reason behind the rule. In fact, include him in the "framing" of your household rules.

CUSTOMIZING YOUR CR’S EDUCATION

The CR learns best by doing. If he can put his hands on it, he’ll master it. You will find an overflow of Concrete Random learners in music, art, athletics, drama, mechanics, and home economics classes. Games, competition, physical involvement, and freedom to act bring out the best in a CR. Parents and teachers using short, dynamic presentations and audiovisual aids will keep his attention. If a CR has several options from which to choose and then full control of his own project, he will bloom. Since boredom is the CR’s worst enemy, these approaches keep his creativity, resourcefulness, and unpredictable nature channeled in positive directions.

Action-oriented and a visionary, a CR dislikes projects that require considerable planning, detailed records, formal reports, or complicated procedures. Once he has finished an assignment, he balks at redoing it. For example, writing a composition requires several steps of editing which irritates a CR. (Doesn’t everyone know that the first draft is the finished product?!) Workbooks, pencil and paper tasks, and routines bore him to tears, while restrictions and limitations without options stifle him. The fastest way to bring out the worst in a CR is to put him in an "educational straight jacket" – a system that is intolerant of innovative ways to challenge the Concrete Random learner. Tip for help your CR:

READING:

Prefers: Exciting/humorous stories

Needs help to: Concentrate on phonics rules, analyze stories, and reading nonfiction

Tip: When teaching how to read, choose a program that uses games, action, and songs.

WRITING:

Prefers: Stories and poetry (creative writing)

Needs help to: Tackle reports and research-related writing

Tip: They do not do well with a typical, structured textbook for a language arts curriculum.

MATH:

Prefers: Math games; short, varied tasks; practical application; reward system; manipulatives

Needs help to: Do pencil and paper work, develop longer attention span, and do long word problems

Tip: They are very competitive with math games. Many math programs incorporate manipulatives/games into the learning process.

SOCIAL STUDIES:

Prefers: Heroes and adventure; wars in history, action stories, dress-up and acting; travel; map making (especially three-dimensional); making simple dioramas or projects.

Needs help to: Tie together events, people, and places and to understand the relevancy of history to us today.

Tip: Read biographies and historical fiction; avoid dry textbooks. Plan lots of field trips.

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Short, hands-on experiments; outdoor activity; active field trips; life science and wildlife studies

Needs help to: Work with scientific data and work on longer term projects

Tip: Avoid a structured, textbook approach; use a curriculum that involves hands-on learning.

FINE ARTS:

Prefers: Varied, short projects; different media; paper construction; drama and dance; music (usually plays by ear); singing.

CONCLUSION

If a doctor diagnosed your child with ADHD, it might be wise to seek a second opinion. Some doctors do not thoroughly test the children – beware of their diagnosis. Your child may simply be a stressed out CR who has never been appreciated for who he is. Most of us can sit still for long periods and handle monotony, but for a CR – whose life is an adventure – boredom is a prison sentence from which he is determined to break out! According to Cynthia Tobias in The Way They Learn, parents can lessen a CR’s stress by (1) lightening up without letting up, (2) backing off and not forcing the issue, (3) helping him figure out what will inspire him, (4) encouraging lots of ways to reach the same goal, (5) pointing him in the right direction and then backing off (the degree you back off depends on the age of the child), and, (6) most importantly, conveying love and acceptance no matter what. Although your CR’s “feet march to the sound of a different drummer”, allowing him to be himself and appreciating his differences will be the "fertilizer" he needs to grow and blossom into a secure, productive adult.

CONCRETE SEQUENTIAL LEARNER

James is home schooled. His mother stays busy with five children, of which James is the oldest. Conscientious and dependable, James is the least demanding of the children. Early on, Mom noticed that he prefers workbooks to multi-age unit studies. As long as his work space is quiet and clean (which means away from younger siblings), James methodically works through his assignments. Because doing his work correctly is crucial to him, James frequently asks for clarification on instructions. Therefore, to avoid interruptions, Mom never leaves James with an assignment until she is certain he understands. Although James devours facts and churns out perfect scores on exams, he struggles in areas that require abstract thinking. Reading between-the-lines puts him in a cold sweat. If you just give him the facts and let him deal with literal meanings, he’ll even hum while studying! Academically, mass education is designed for Concrete Sequential (CS) learners like James, but he’s happy at home, learning at his own pace and developing values important to his family.

A no-nonsense person, a CS learner sees the practical side of issues. When he speaks, he is never subtle, but goes directly to the point. Not one to quit in the middle of anything, he will finish whatever he is doing even if he hates it. This is because a CS has a sense of order and responsibility that requires a beginning, middle, and an end. Nearly as predictable as the sunrise, you can always count on a CS to follow through. Although not naturally creative, he excels at fine-tuning and improving another’s original idea. A list-maker and organizer, he thrives on a schedule. Consistency is his byword.

Routine is important to a CS learner. When unexpected changes occur, he struggles to adapt. While it is important that he understand life cannot always be predictable, if possible, give him advance notice of a change in plans. Never just tell a CS what to do unless he is already familiar with the task. Provide concrete examples of what is required because vague directions do not register. Often overwhelmed with too much to do, he becomes frustrated by not knowing where to begin. Ask him how you can help him. Sometimes helping him to list priorities is all he needs to get going. While CR or AR learners almost relish clutter and noise, a CS learner’s ability to concentrate freezes in such an environment. If you provide a specific time for uninterrupted work in a clean and quiet place, he’ll sail through his assignments comfortably and come out smiling. He delights to accomplish his goals and check them off his list!

CUSTOMIZING YOUR CS’s EDUCATION

CS learners flourish in math, spelling, history, geography, and business subjects. He relishes drills, reviews, memorization, and thrives on workbooks, structure, and routine. Lectures and outlines neatly place all the facts in his orderly mind to draw out when needed. His mind is a splendid time line! A CS has an innate need for order and a propensity for perfectionism. Because of these traits, he learns best by following an example. Although not too fond of discussions or oral reports, he will excel if given enough time to prepare. Role playing and dramatization, however, are not his forte. He can churn out reports replete with all the facts, but imaginative writing draws a blank in him. Nonetheless, even the driest CS learner can be taught to think creatively. Tangible rewards and hands-on methods motivate him. If you wisely and gently use these types of motivations, you will watch a CS gradually unfold to a new world of creativity. Tip for help your CS:

READING:

Prefers: Phonics, programmed reading, word lists, and oral reading (if they are prepared)

Needs help to: Read from context and read beyond the literal meaning

Tip: Will do well with most phonics programs. Practice oral reading in a nonthreatening, relaxed setting.

WRITING:

Prefers: Handwriting drills, worksheets, and well spelled-out assignments

Needs help to: Write creatively

Tip: He will do well with traditional language art textbooks. For creative writing, though, use "story starters" or books that deal specifically with creative writing.

MATH:

Prefers: Workbooks, programmed math, and drill

Needs help to: Apply arithmetic to word problems that require abstract thinking

Tip: He will do well with most math textbooks

HISTORY:

Prefers: Names, dates, making maps and time lines

Needs help to: Read biographies, historical fiction, and novels that give life to these subjects.

Tip: Because a CS thrives on the details, they miss the big picture. Find creative ways to show him how the details fit together in the overall message. (Read biographies and historical fiction aloud as a family.)

SCIENCE:

Prefers: Science notebooks, collections of leaves, rocks, etc., programmed book learning, and sciences that are less speculative (biology, botany, and physiology)

Needs help to: Form hypotheses and do experiments

Tip: Plan creative projects that let him express his aptitude for details and facts.

FINE ARTS:

Prefers: Art - drawing with clear directions to follow, photography, and crafts;

Music - note reading

Needs help to: Bring out his own creativity

Tip: Drawing with Children by Mona Brooks is an excellent resource that equips the ordinary person to teach art. It teaches how to analyze everything you see so that you can know how to draw. It also includes painting instructions. This style would work well with a CS learner.

CONCLUSION

Your CS learner is the most goal-oriented of all the learning styles. Some will accuse him of tunnel-vision, but this mastery at maintaining focus and drive to fulfill the goal provides our world with men and women who routinely accomplish ordinary and history-making achievements. This trait, however, causes a CS to value things and responsibilities more than people. Knowing this, parents must teach their CS that life does not solely consist of attaining goals; he needs to understand that it is okay to take time for people, too. If necessary, let him schedule time for family and friends on his calendar. He may even feel that he "accomplished" something when he checks it off his list!

As a perfectionist, he will thoroughly fine-tune an idea or project. You can help him to not take himself and life too seriously by teaching him to laugh at himself and the inevitable imperfections of life. Encouraging him to practice patience with the people in his life will make him amiable, also. A slave to routine, your CS is uncomfortable with change. You can rejoice that this characteristic enables you to count on him, and, at the same time, gradually introduce circumstances that require him to adapt. While it is important to teach your CS to relax and enjoy life, remember to appreciate him for who he is: serious, practical, and predictable.

On Monday your son was given a list of twenty-five new words to spell and define by Friday. How is he going to master the words so that he remembers them? Will he put them on flash cards complete with word-association pictures? Perhaps he will record the spelling and definition of each on a cassette to listen to while he does his chores at home. He could even tape the words on twenty-five different pieces of furniture all over the house, timing himself as he races to each word. These are examples of the three basic ways of remembering information: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. We all use each in varying degrees, but will have one style that dominates how we remember. Use the following chart by Cynthia Tobias (The Way They Learn, p. 90) to decide whether you and your children are auditory, visual, or kinesthetic learners. (If you are still unsure which style you are after checking the chart, try out each approach until you find one that fits you.)

WHY LEARN?

Most of us forget 80% of what we learn within three months and even a higher percentage after that. Why, then, should we bother going through the agony of learning? If the process is so inefficient, why not channel our efforts in more productive ways?

Learning provides us with basic literacy and math skills. Without these tools, we are handicapped in performing the simplest tasks in our daily lives. Imagine not knowing how to read. We would be dependent on others to keep us informed of not only current events, but also information pertinent to our day-to-day responsibilities. Dependency on other people for information leaves us vulnerable to their prejudices and values. Basic math skills enable us to budget our finances, count change from the cashier, and balance a check book. Buying and selling houses and vehicles is a part of most everyone’s life. Where would we be without the competence to handle these transactions? Although usually mastered in elementary school, these skills carry a lifetime of applications.

The mental process necessary to learning develops self-discipline, a character trait desperately lacking in our contemporary society. The good student learns to sit for long hours, follow directions, carry out assignments and redirect his mental faculties. Self-discipline affects every area of our lives: employers can trust us to do a job without supervision, we can shop and stick to our list (Yes, we made a list!), we can stop eating when full and say no to that extra portion, and we’ll even submit our work reports on schedule. If we only remember 20% from the long hours of study, the self-discipline gained would alone be worth the effort.

When the studied details are long forgotten, our lives are often changed by what we learn. We assimilate altered values, new attitudes, and different concepts into our lives that do not fade with time. No student ever remembers everything he learned in school, but he becomes a very different person after faithfully pursuing those studies.

Once we complete a learning process, although we may not recall all the information, we do know that those facts exist, and we know where to find them. It is not necessary (or possible) to always know the answers to the problems and questions that face us, but it is important to know where to find the answers.

We don’t forget 100%. Our permanent memory stores the most important information for future use. Amazingly, the brain amasses two billion bits of data in a lifetime. Because of the educational process, our memory bank is filled with useful information.

Old learning makes new learning easier. The mental exercise offers more associative cues with which to link future ideas. For example, once you’ve learned your alphabet, you associate it with the process of learning to read words. A lazy mind is a boring mind. Learning stimulates the brain and keeps us mentally alert. Challenges keep us thinking and growing. Sadly, elderly people who quit challenging their minds often develop senility.

No matter how much information one retains, the learning process provides more value than meets the eye. The slow, painful experience of education shapes the mind and builds character. It is a process we should practice our entire lives. Next time your children protest completing a school assignment, don’t lecture them with the information from this article. Just encourage them to keep plugging away. Then save this article and hand it to them when they have their own children.

Learning provides us with basic literacy and math skills. Without these tools, we are handicapped in performing the simplest tasks in our daily lives. Imagine not knowing how to read. We would be dependent on others to keep us informed of not only current events, but also information pertinent to our day-to-day responsibilities. Dependency on other people for information leaves us vulnerable to their prejudices and values. Basic math skills enable us to budget our finances, count change from the cashier, and balance a check book. Buying and selling houses and vehicles is a part of most everyone’s life. Where would we be without the competence to handle these transactions? Although usually mastered in elementary school, these skills carry a lifetime of applications.

The mental process necessary to learning develops self-discipline, a character trait desperately lacking in our contemporary society. The good student learns to sit for long hours, follow directions, carry out assignments and redirect his mental faculties. Self-discipline affects every area of our lives: employers can trust us to do a job without supervision, we can shop and stick to our list (Yes, we made a list!), we can stop eating when full and say no to that extra portion, and we’ll even submit our work reports on schedule. If we only remember 20% from the long hours of study, the self-discipline gained would alone be worth the effort.

When the studied details are long forgotten, our lives are often changed by what we learn. We assimilate altered values, new attitudes, and different concepts into our lives that do not fade with time. No student ever remembers everything he learned in school, but he becomes a very different person after faithfully pursuing those studies.

Once we complete a learning process, although we may not recall all the information, we do know that those facts exist, and we know where to find them. It is not necessary (or possible) to always know the answers to the problems and questions that face us, but it is important to know where to find the answers.

We don’t forget 100%. Our permanent memory stores the most important information for future use. Amazingly, the brain amasses two billion bits of data in a lifetime. Because of the educational process, our memory bank is filled with useful information.

Old learning makes new learning easier. The mental exercise offers more associative cues with which to link future ideas. For example, once you’ve learned your alphabet, you associate it with the process of learning to read words. A lazy mind is a boring mind. Learning stimulates the brain and keeps us mentally alert. Challenges keep us thinking and growing. Sadly, elderly people who quit challenging their minds often develop senility.

No matter how much information one retains, the learning process provides more value than meets the eye. The slow, painful experience of education shapes the mind and builds character. It is a process we should practice our entire lives. Next time your children protest completing a school assignment, don’t lecture them with the information from this article. Just encourage them to keep plugging away. Then save this article and hand it to them when they have their own children.